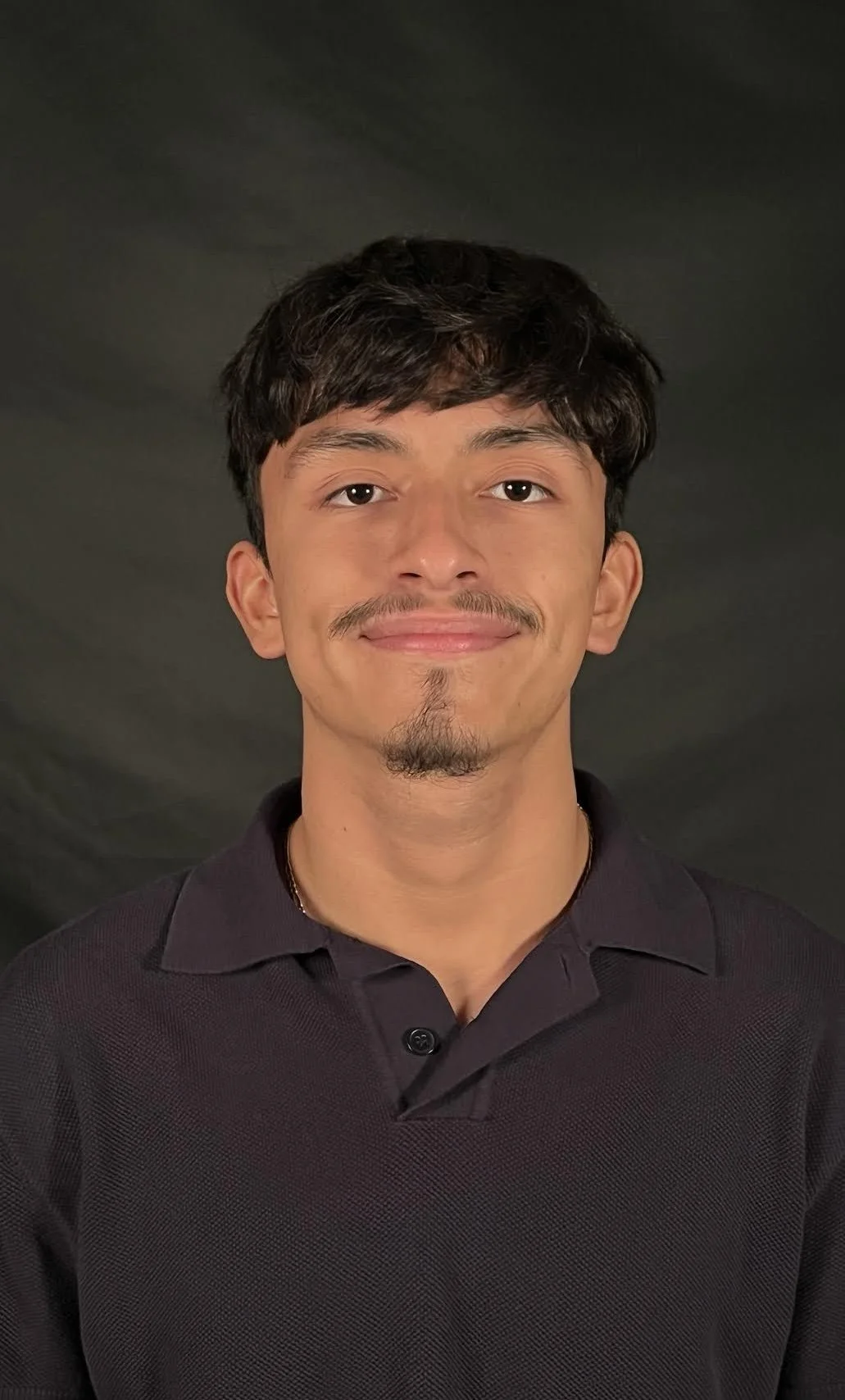

Colseguros

Thomas Diaz ‘25

Colseguros consists of two superimposed images derived from two disparate places. The foreground depicts my family resting on my mom's car, here in America, while the background depicts my childhood neighborhood in Colombia called Colseguros. The juxtaposition of both images aims to remediate a fractured immigrant identity through a hopeful fabrication of a memory that could have been. Setting moments I experience in America in Colombia allows me to express my desire to consolidate a fractured cultural identity.

Flesh and Ink: A-125, A-164, A-209

The names go first.

No announcement. No explanation. Just absence.

At roll call, the teacher’s voice catches for half a second,

eyes scanning the list,

pen hesitating over letters that suddenly don’t belong.

She swallows, moves on.

By the next day, she doesn’t pause at all.

A desk sits undisturbed,

its surface still marked by last week’s restless hands—

shiny patches where palms rubbed too often,

tiny carved lines from the tip of a pencil pressed too hard.

Inside, a gum wrapper, folded into a perfect square.

A loose paper clip, slightly bent.

A page torn from a notebook,

the words trailing off mid-sentence.

At the lunch table, a half-empty water bottle remains,

condensation pooling into a damp ring on the plastic tray.

No one reaches for the abandoned orange,

its peel dimpling under the fluorescent lights.

No one laughs at the joke scrawled in Sharpie on the table’s edge,

the one only they thought was funny.

At the bus stop, the 5:42 pulls up,

the doors sighing open to the dark.

The driver glances toward the curb, out of habit,

expecting the usual figure—

the hurried step forward,

the shuffling through a backpack for the right change.

Nothing.

The driver lingers for a second longer than necessary,

as if waiting for the city to correct itself.

Then, the doors shut, and the bus moves on.

The apartment door is left ajar.

Inside, the smell of coffee lingers,

a mug sits on the counter, half-drunk, the surface cooled to a film.

A blanket is twisted at the foot of the couch,

a single sock curled beside the leg.

In the bathroom, a toothbrush leans in its cup,

bristles still wet.

A closet stands open just enough

to show empty hangers swaying slightly,

as if someone left in a hurry,

as if the air still remembers movement.

Outside, the landlord scrapes a name from the mailbox slot,

pressing the edge of his thumb against the stubborn ink.

It peels away in uneven flakes,

leaving behind a faint smudge,

the memory of a presence.

At the bakery, an old woman kneads dough in silence,

her hands moving out of habit,

but her eyes flick toward the door every few minutes.

For years, she packed the same order,

a concha wrapped in a napkin,

a coffee with too much sugar.

Now, she stops short before reaching for the paper bag.

She folds it anyway,

sets it aside.

At the bodega, the cashier dusts off the cans of mango Jumex,

noticing the fine layer of untouched time settling over them.

No one asks for a scratch-off ticket with a smirk

or taps their fingers against the counter while counting out change.

The city does what it always does—

keeps moving, keeps swallowing absence like a machine.

Jackhammers erase footprints.

The apartment door swings open for someone new.

Paint rolls over the faint pencil lines on the wall,

the ones that measured birthdays in inches,

growing in careful marks.

But something lingers.

At night, when the neon signs buzz softly in the dark,

when the streets are empty except for the occasional shadow,

there is a space where something should be.

A voice not speaking.

A footstep not taken.

A breath held just a little too long.

And then—

The whispers start.

Neighbors glancing away,

hands tightening around shopping bags.

Someone mutters it at the laundromat,

just barely audible above the hum of the dryers.

Gone.

Not moved. Not left.

Gone.

And the city does not ask why.

London Franklin ‘26

My inspiration for this piece was the current uproar in tension surrounding deportations in America. As someone who is a second generation American, the topic is one that I find extremely poignant and rich in discussion for the blending of human rights with politics and morality. The catalyst for the writing of this poem was the official White House X account posting a Valentines Day card reading, "Roses are red, Violets are blue, come here illegally, and we'll deport you."